Program: US Government EPA West Coast Labs

Size: 28,000 Sq. Ft.

Location: Santa Monica, California

Year: 2019

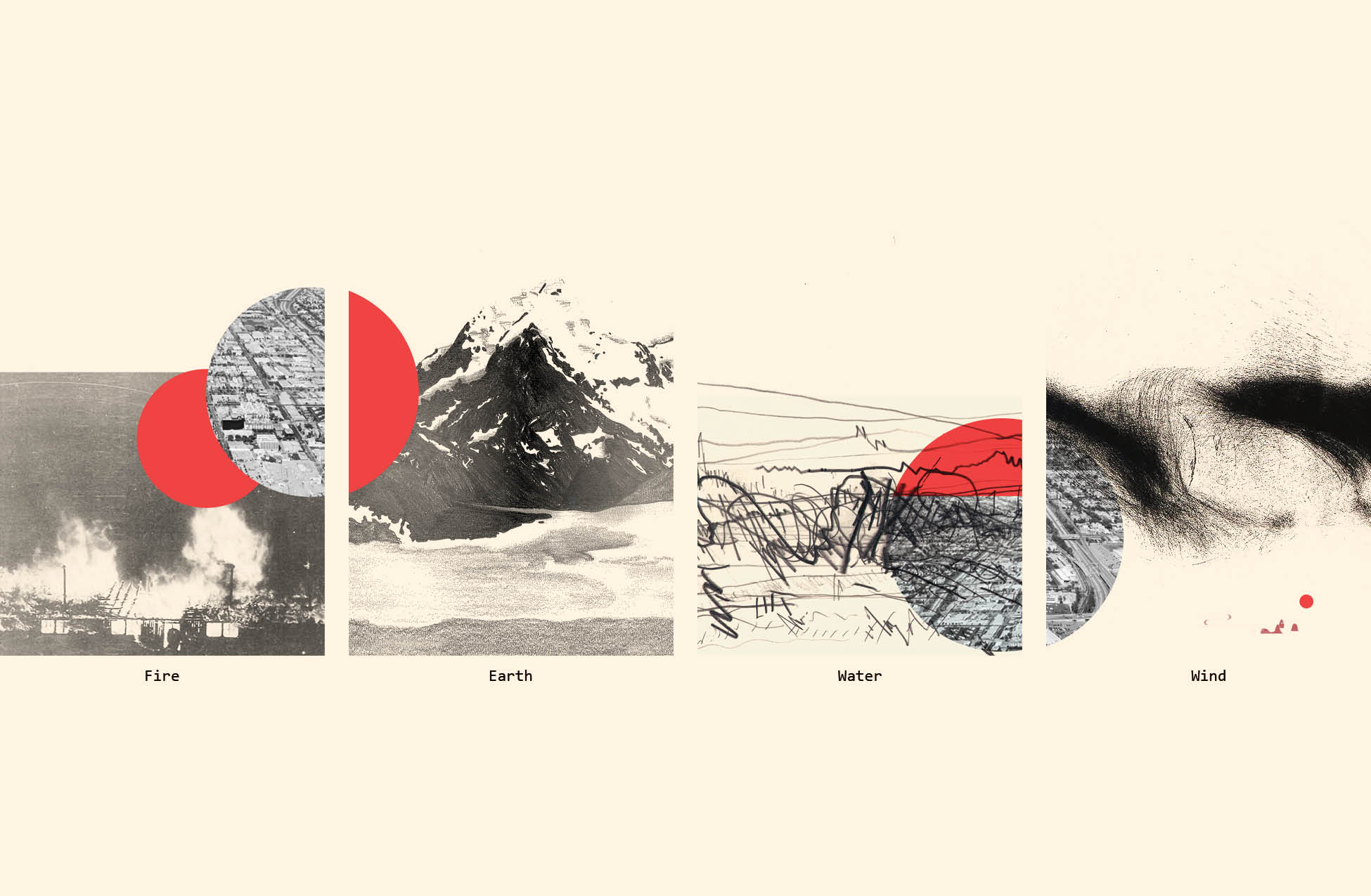

“Man-made accidents,” “high risk of natural disasters,” “complex cluster of accelerated systems” — these are phrases that characterize Los Angeles. The stakes are high and the response places a lot of emphasis on architectural implementation. This project is an attempt at minimizing the building and construction process; it treats the architecture and design as secondary to the site.

As an urban organism, Los Angeles struggles with poverty, homelessness, economic injustice, and climate change. Architecture and urban development have been catalysts to these inbalances but they are only one side of the story. Like most of the United States, Los Angeles needs to address its legal system and question its treatment of nature. Arguably one of the greatest sins of Western society is that it never incorporated the natural world into its own legislation. After having dispossessed Indigenous populations from their lands and subsequently undermine their knowledge and success through cultural domination, it is no wonder that White colonizers eliminated any ethical standard when it came to their relationship to the environment. Western culture from its education to its implementation fails to understand its own ecological network and thus, refuses to back it with any reliable and responsive legal system rendering it powerless against industry. A culture that understands nature as property and ignores its rights as a non-human entity directly leads to catastrophe. The current model is antiquated and still recalls ideals of “domination and exploitation that allows humans to be separate and superior to the Earth.” (Cormac Cullinan, environmental attorney and author of Wild Law, 2002.)

Corporations, trusts, charities and nation states already have legal personhood and the right to own property; to have legal standing; to sue or be sued in court, etc. In the 21st century, we have precedent for nature’s rights, such as Lake Erie in Ohio or the Yamuna River in India, which all have lawful advocacy. Yet our society supplies no consistent legal recognition or respect. If we were to ordain land with human legislation and entitled its identity as a living being with all its ecological complexity, development—when it uses construction operations to abuse nature—could be thought of as illegal. Within contemporary development, it is hard to ignore any such consequences when it is so visually present. How can certain assumptions not be made when looking at a suburban city, such Los Angeles, that suffers so dramatically from the climate crisis and extreme inequities among its inhabitants?

The current statement put out by the EPA reads, “Our mission is to protect human health and the environment.” Note that here the focus is on anthropocentric concerns when it should consider humans as toxic entities when protecting our now extremely fragile environment.

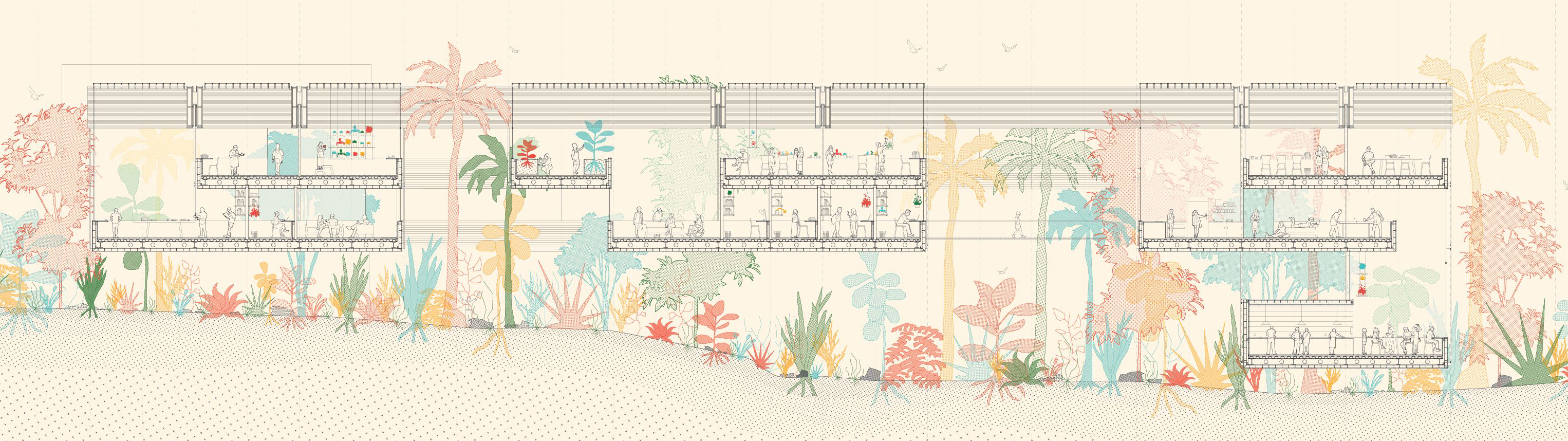

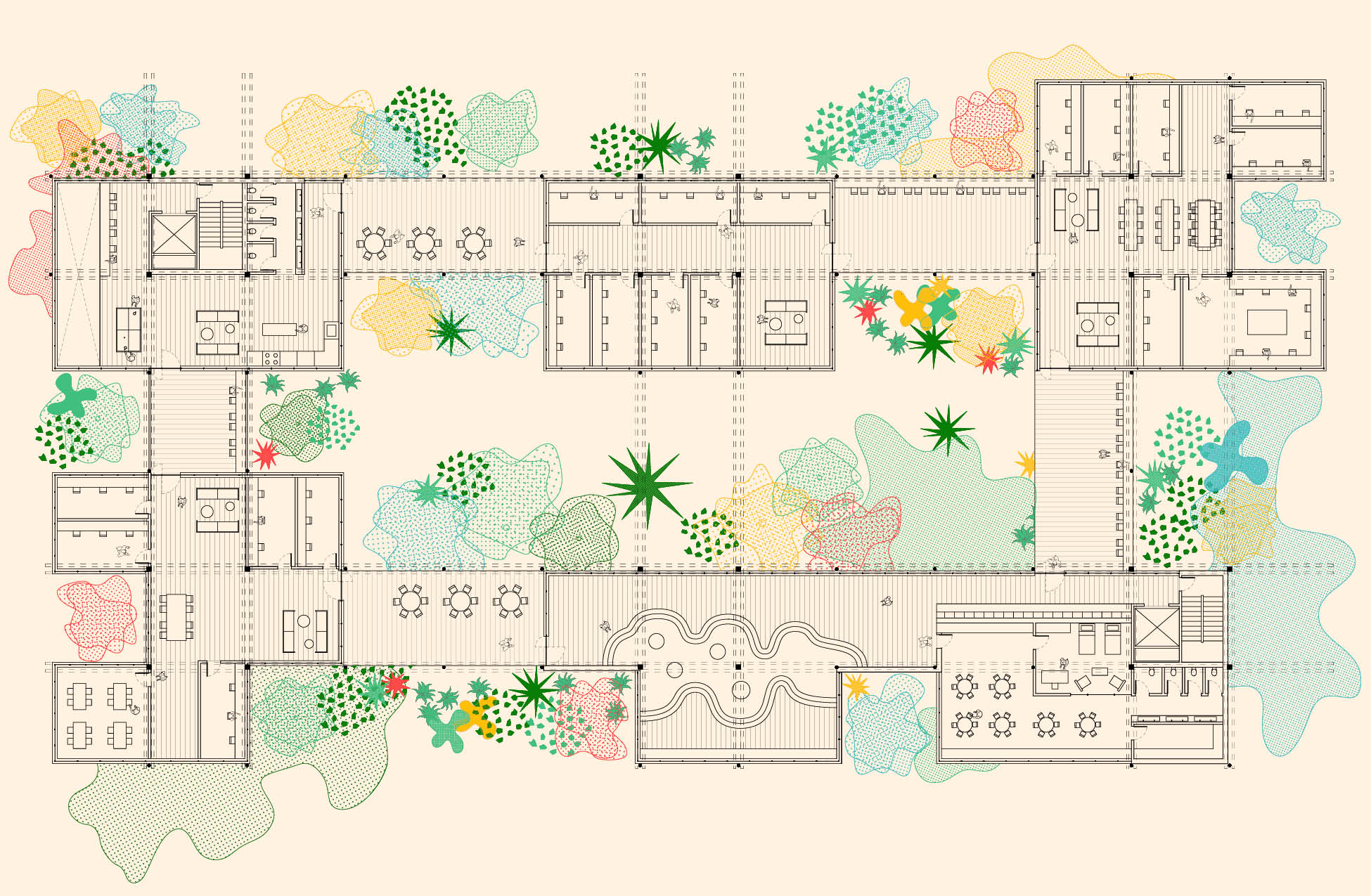

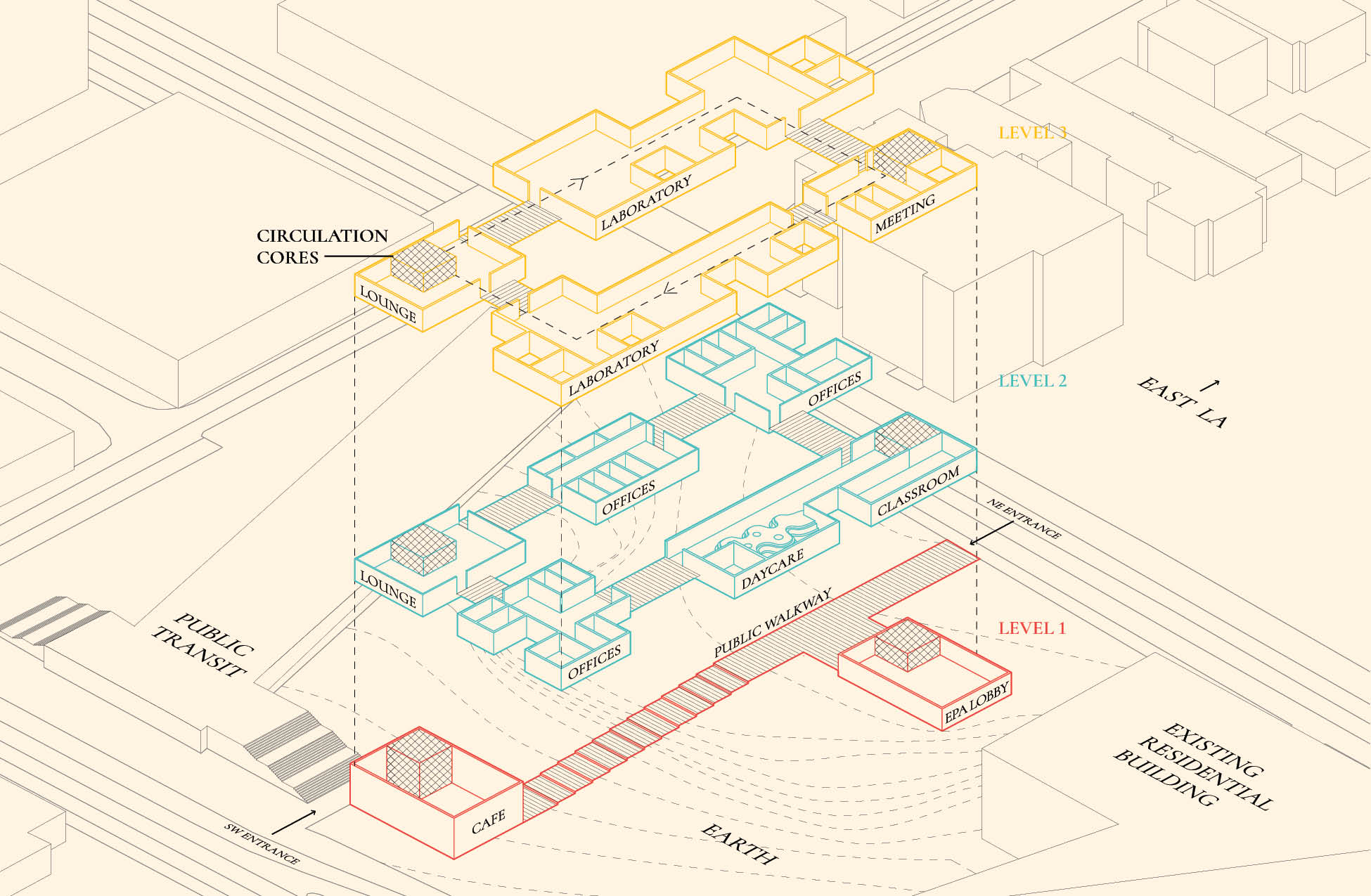

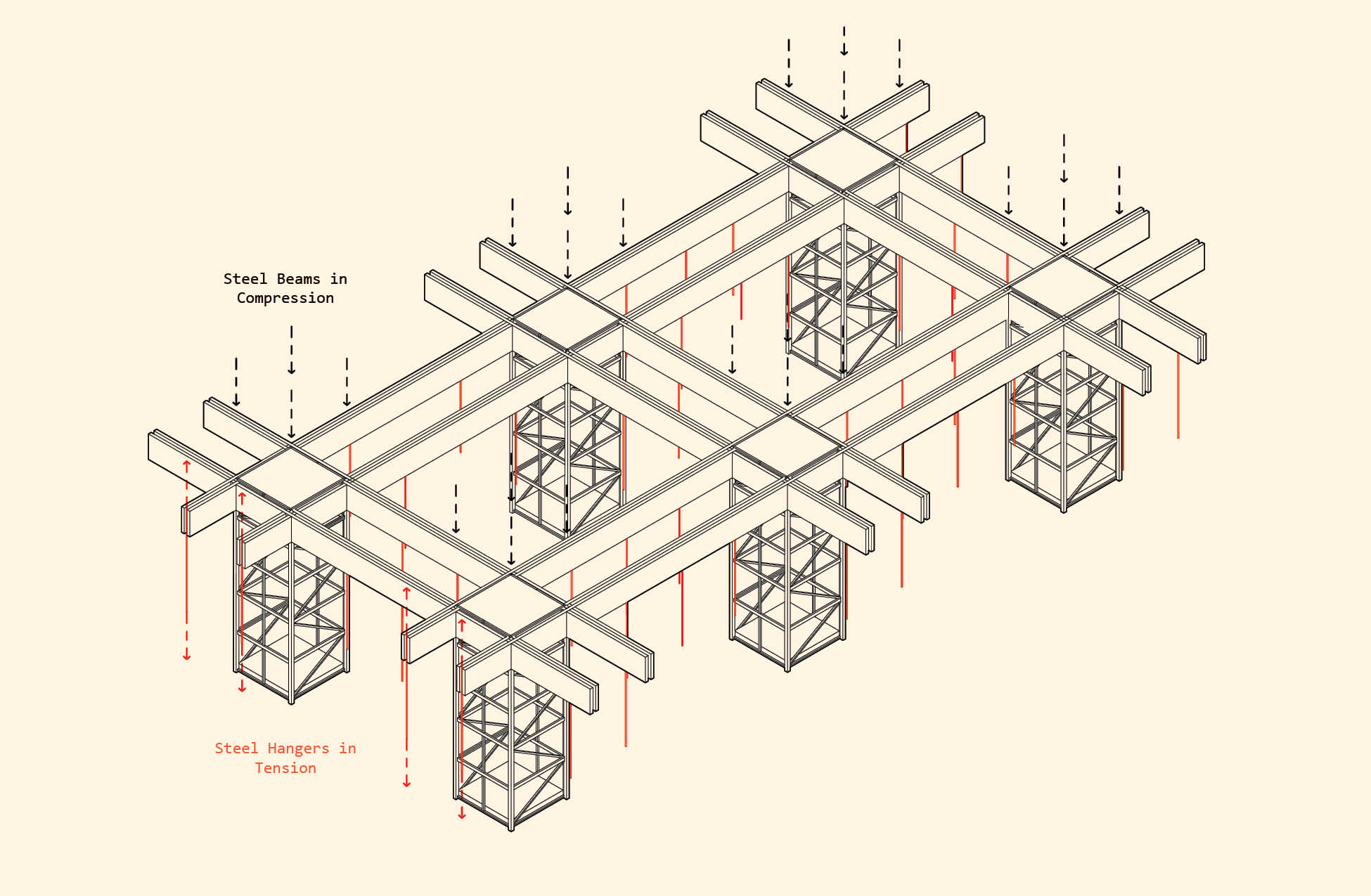

Spurred out of ecological disaster brought on by the malicious behaviors of American capitalism and its legal system, this project is dedicated to a new form of environmental protection that prioritizes a restructuring of legislation and society. Located in urban Santa Monica, seven blocks from the ocean, this is a facility for collective thinking and experimentation that stimulates social interactions and community responses to nature’s needs. The design and materials of the building were sensitively implemented to advocate for a proper understanding of nature’s equal rights to personhood. Constructed on a structural hanging system, the building is lifted off the ground allowing the natural ecosystem around it to thrive. In a sense, the building is a parasite—stripped of its associated figure-ground relationship and hovering within an oasis. Its lightweight and recycled poly-carbonate and steel materiality go so far as to even question its own existence. The circulation runs in a loop framing a courtyard, expanding and contracting, opening and closing, going from interior to exterior pathways, allowing plant and tree life to intersect with human activities while calling for respect.

Project 2

New Obsessions: The Baltimore Wood Project

Program: Public Woodworking Studio and Urban Forest

Size: 100,000 Sq. Ft.

Location: Baltimore, Maryland

Year: 2018

This project began by examining the complex relationship between the human psyche, addictive substances and the global economic world system. Americans in particular have been modified drastically to fit our ravenous capitalism; as the world's superpower, the United States is always at the forefront of commodification techniques from sugars to cocaine to opioids. Corrupt politicians shaking hands with powerful corporations lean on poverty and dehumanizing tactics to inspire the rich. While many cities remain relatively stable as a result of this excessive competitive nature, some have become unlucky examples of America’s failure to temper its appetite for consumption. With high unemployment rates and slow job growth, Baltimore’s population has had no choice but to turn to black-market modes of income to survive. Through urban flight, the culture has triggered almost 30,000 vacant homes in the city. Not only are communities suffering but they are disappearing as row houses, infrastructure, and urban foliage are abandoned.

The Baltimore Wood Project, an existing program that began in 2017 threads together the social and environmental dynamics of a city by training residents to salvage wood from buildings flagged for demolition in the hope that the city might see a new economically and environmentally stimulating purpose to their urban decay.

This studio project aims to support this program by introducing and reimaging an archetypal socialist architecture--the Soviet workers' club--as a way to elevate the culture of purposeful woodworking and urban forestry. In 1920s Russia, the workers’ club provided individuals and families with opportunities for recreation and education. Although they ultimately propagated detrimental political ideals, (unfortunately more fascist than socialist), the clubs were meant to be places of community and discourse by offering a broad range of spaces - the Working, Living, and Social.

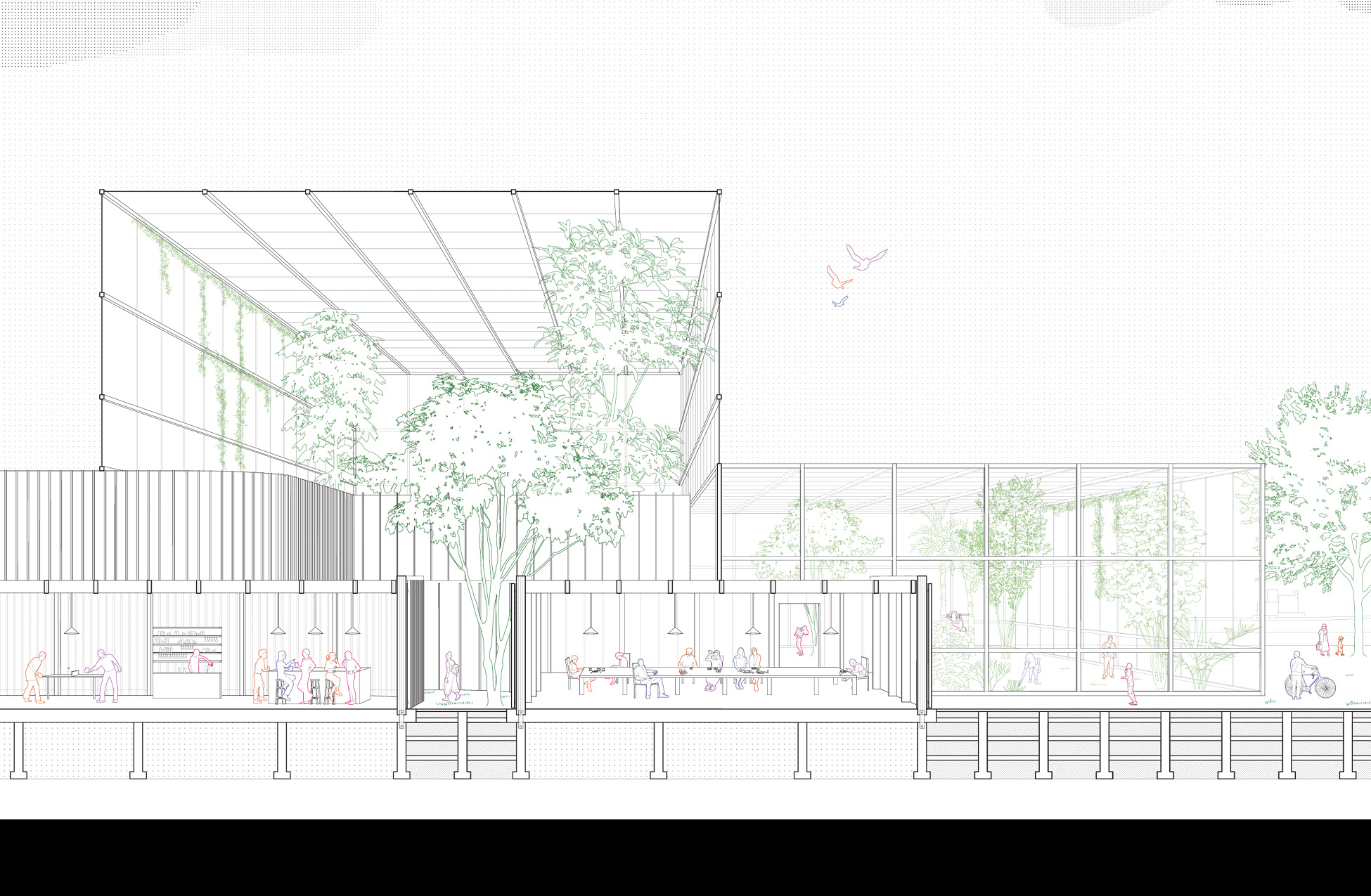

This building would become the headquarters for the Baltimore Wood Project; a 100,000 square foot woodworking studio and community center with temporary living quarters for those in need while training to become skilled craftsmen.

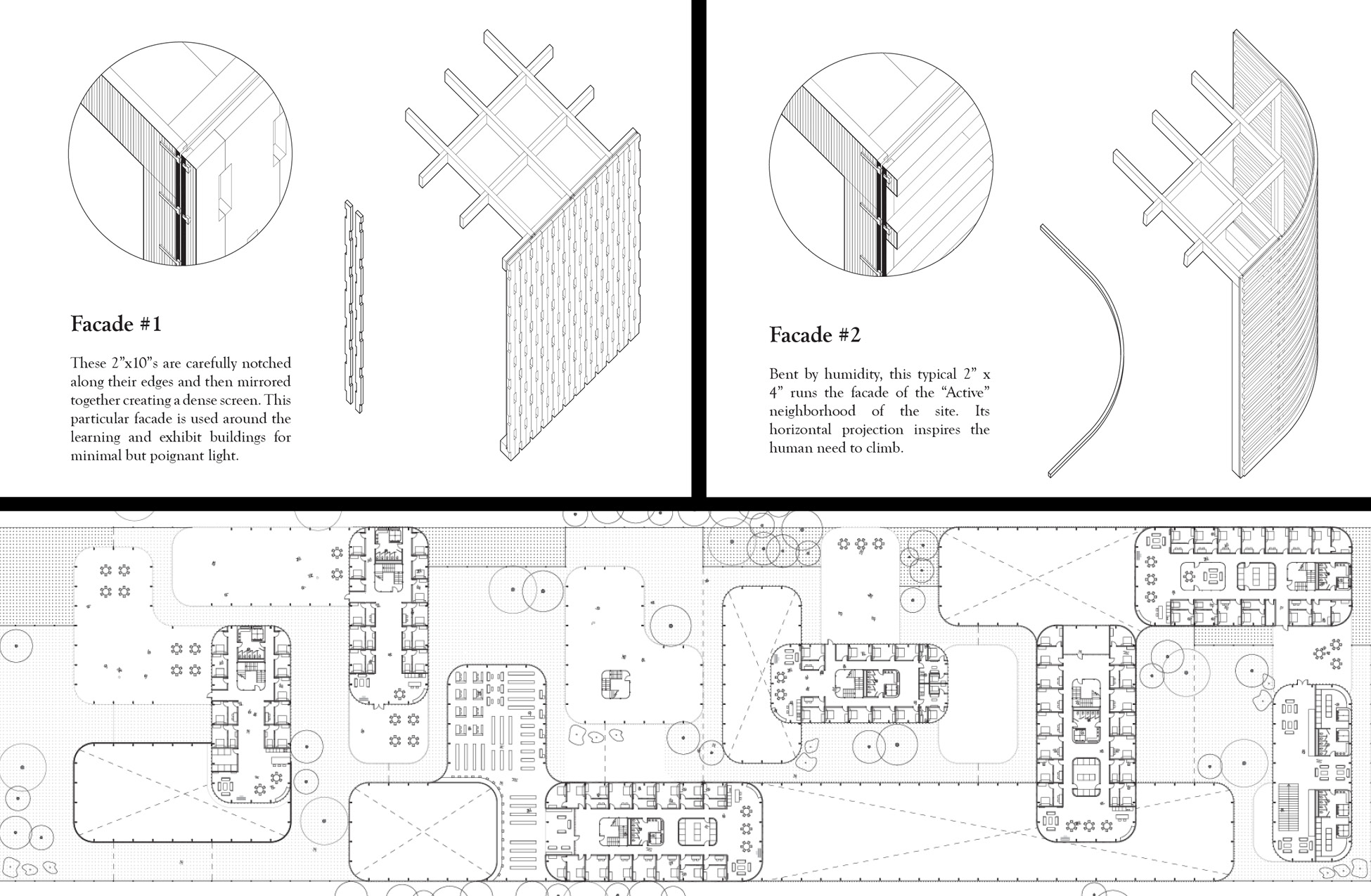

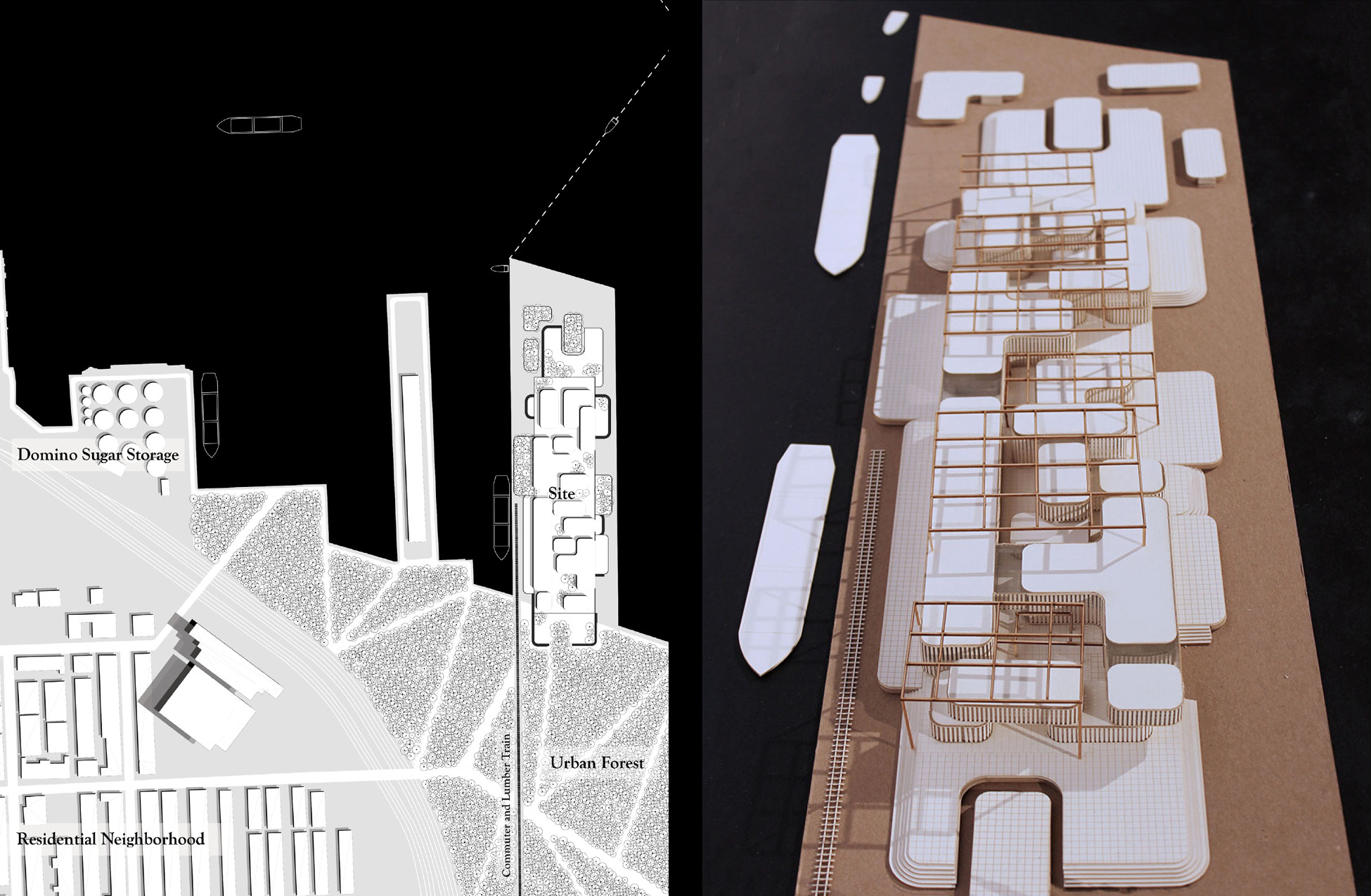

The project site is in the heart of the industrial neighborhood of Locust Point, Baltimore, where corporations and shipping docks sit along the waterfront, blocking the residential community from the harbor. To return waterfront access to the community, an urban forest would provide clear pathways and recreational spaces while also mitigating CO2 emissions from the nearby industrial sites and highway. Within the building itself, there are four main formal objectives: 1. To foster both collective and individual experiences: circulation expands and contracts creating both plazas and alleyways. 2. To ensure that all spaces remain pure--soft corners, copious plant and tree growth, sunlight and warmth are prioritized. 3. To allow the occupant to determine what is important to their own lives, thus spaces and program lack formal hierarchy. 4. To support productive lifestyles, Working, Living and Social spaces are separated but interlocking in order to be both focused and influential to one another.

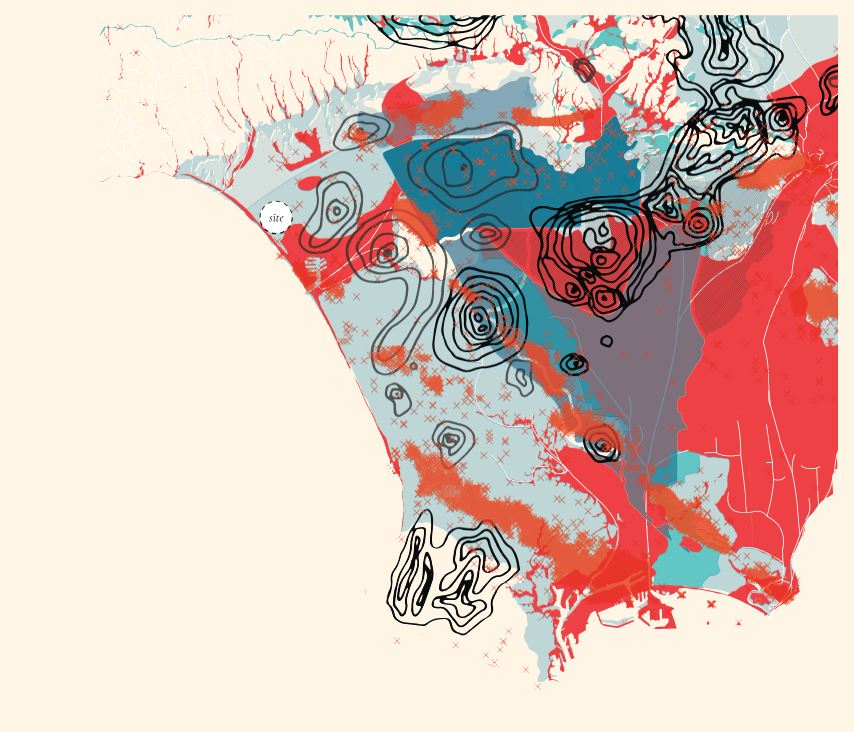

The Baltimore Wood Project uses lumber from two main sources. The site has just over 30 acres of an urban forest with four types of wood species - Black Locust, Red Maple, Loblolly Pine and Cherry - that are to be incrementally cut down for wood production. The second source is the wood salvaged from the "unofficial estimate" of over 30,000 vacant buildings in the Baltimore area. Shown in the map to the right are all the vacant building footprints, as well as five highlighted locations that could be used for other worker palaces.